Blue Ocean Strategy: A Review

I am reading Blue Ocean Strategy (Expanded Edition) by W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne. It is solid gold and I wish I’d read it 10 years ago. The thing that surprises me most here is that nothing in here is “new”. Apart from the case studies (which are excellent), I could not put my finger on a single principle or idea that was unknown to me, but the way that it recombines existing ideas into a framework is excellent.

I think of it as some sort of weird evolution of Porter’s Five Forces, as well as the opposite side of the coin of Marty Cagan’s Inspired. Cagan advocates for talking to customers systematically to learn what they want (bottom-up approach). Blue Ocean talks about looking at the industry and competitors structurally to reinvent market boundaries and find areas without competition (top-down approach). The thing that I find most interesting about this book is the idea that there is a systematic way of generating innovation and identifying areas without competition, and that it is consistent across (an extremely wide range of) companies and industries.

The essence of Blue Ocean Strategy is this:

You can unlock a dramatic step-change in value creation by finding areas without competition to operate in (duh), and those opportunities can be identified systematically (aha).

Most companies in every industry tend to compete on 6 or so common factors – price, convenience, quality, brand perception, etc.

Companies that find new areas of value to exploit (“blue oceans”) typically find 2-3 of these elements to excel at, ignore the rest, and add several more elements hitherto unknown to the industry. Costco competes on scale and price, doesn’t care about convenience, and invented subscription sales as the way to monetise.

To find new areas of value creation, successful companies tend to follow a 4 step process:

- Eliminate (what is not necessary that we can do away with)

- Reduce (what still needs to exist that we don’t need as much of?)

- Raise (what do we need to improve to compete here?)

- Create (what do we invent from scratch to unlock that blue ocean opportunity?)

Here’s an example from Casella Wines, which is Australian and whose Yellow Tail wine is (apparently) one of the most successful wines in the world:

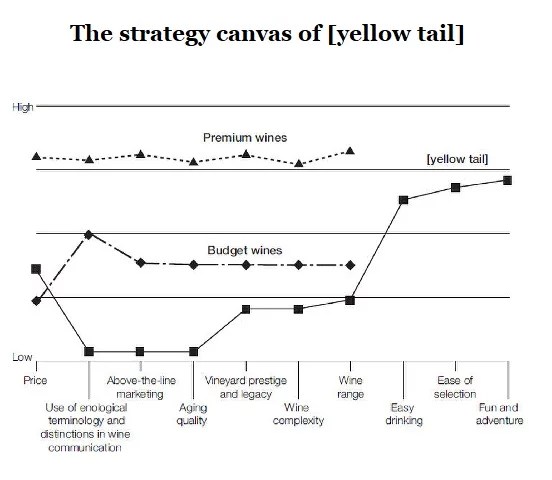

Another way to look at this is Casella’s strategy canvas versus the rest of the industry. It ignores several factors and invented new factors to compete on:

There is a systematic way of looking for ideas to create these “blue ocean” opportunities:

- Look across alternative industries. Financial software, accountants, and DIY all compete for the same thing – “help me do my taxes” – even though they are often treated as being different industries and viewed as such. The traditional approach is to think that accountants and financial software are not in the same industry (“services” vs “information technology”) but actually they both aim to solve the same problem for the customer and are therefore the same thing. I oversimplify, but I hope that illustrates the point. (This is where a jobs to be done approach may come in handy – Cagan’s book is a better fit here).

- Look within and across strategic groups in your own industry. Automotive brands used to be split into mass market (Toyota) and upmarket (Mercedes) with the industry competing on price and quality. This created opportunity to create “masstige” (mass market prestige) brands like Lexus that were a mix of factors – higher quality and exclusivity at a higher price, but not as expensive as a Mercedes. (This is probably one of the weakest examples in the book in my view as it is still basically competing on the same factors – price, quality, exclusivity – as the rest of the industry, but hopefully the point holds).

- Look across the chain of buyers. Who is the end buyer of the product? In many cases it’s the person that pays the money, not the user. Simple examples are parents buying toys for their children or a purchasing arm of an organisation buying software for its teams. There are advantages to be gained when the pendulum swings too far in either direction (a toy that focuses too heavily on marketing to parents may be unwanted by children, for example). This is probably the weakest point in the book as it’s well covered in basically any book on business, but it’s correct nonetheless.

- Look across complementary product and service offerings. Probably the second weakest point in the book and it is covered in part by the “emotional & functional aspects” point below. What do people also buy when they buy your product? It’s not as simple as “new phone” and “headphones” but more complicated like what can you do with a phone and therefore what other services do you need (telecoms have latched onto phone and internet, for example). There’s not a lot of value in this point, if only because most consumer industries, including software and ecommerce, are all over this approach already and there are better books out there.

- Look across emotional & functional aspects of a business. Does the product serve a functional need (“do X thing”) or does it serve an emotional need (status signalling, providing trust and recourse, etc). A common trend is for emotion-laden purchases to become more functional (e.g. financial services like banking and accounting that were built on reputations, becoming more automated and functional) and vice versa. The example given was Cemex in Mexico setting up a program to make purchasing cement an emotional purchase (“building a future” as opposed to “buying a bag of cement”) that was incredibly successful at growing the business and improving its financials. You can see this idea playing out with brands everywhere.

- Look across time. Look at the product life cycle to gain insights. Many products are not a “one and done”, but have follow-up requirements in terms of maintenance, repair, updates, et cetera. Often these products are pitched to investors as a positive (“recurring revenue”, “locked-in customers”, etc) but actually these products may be ripe for a reclassification by a company that goes in a different direction. The example given in the book is the invention of the fibreglass bus to greatly reduce emissions and repair costs, while building the bus cheaper to a higher spec. Repeat relationships may be vulnerable to a one and done product, and vice versa. SaaS comes to mind here because the recurring revenue aspect of the business model is so ingrained – it is the holy bible of the industry – I suspect it is likely vulnerable to reinvention and redefinition.

A key idea that is developed in some depth is that technological innovation is not required to create highly profitable niches. It is all about consumer value, and creating a step change in consumer value requires both value and price innovation. I can’t do these ideas justice in a few sentences, but (obviously) consumers want to get more value for less. However, the way value is defined is typically falsely constrained by industry norms (the idea a faster car delivers more consumer value, for example) and that price innovation does not simply mean making things cheaper. In fact many of the examples in the book created huge and obvious consumer value while putting prices up.

Following this, the book progresses into how to identify your current strategy, how to craft a new strategy (hint: talk to customers – Inspired fits in well here), how to position your product in the market, how to price it, how to defend it from customers especially if the idea is replicable and not patentable. As a whole, this book converges massively with Marty Cagan’s Inspired, but they look at the same problem from different perspectives. In my view, Blue Ocean is far more useful for investors.

It’s an excellent book. A business book written by professors just begs to have a price tag put on it and I thought about this for awhile. Gun to my head: The value I got out of this book was at least $500. The consumer surplus is high. I recommend it.

There are no affiliate links in this article and I was not compensated in any way for writing this review.

No Comments