The End of Henry Morgan

Five years ago, I published a series of reports on a group of “pirate” companies after identifying concerns in public filings. Those companies, Henry Morgan (ASX:HML), John Bridgeman (NSX:JBL) and Benjamin Hornigold (ASX:BHD) have each since met their end.

Two were delisted by their exchange operator, and the third (BHD) had management voted out by shareholders and replaced, leading to the recovery of some value and the resumption of trade.

One of the funds, Henry Morgan, was liquidated by court order this year. To this day I still get asked about the story and, given that I removed my original reports on threat of litigation, let this be the abridged version.

Please note: The below is my memory of events and conversations. Others like Sulieman Ravell, Jon Dixon, Michael Glennon, Gary Miller, and Tony Bennett made their own contributions. However, you will have to ask them for their version.

How it started:

In 2016, several investment vehicles were founded and listed on the ASX. The plan was to trade managed futures and currencies, equities, and other listed instruments. The businesses operated in a fund/fund manager structure, where fund management company John Bridgeman provided fee-based investment management services to HML and BHD.

Management and performance fees for HML and BHD were 2 & 23 and 3 & 27 respectively. The Sydney Morning Herald had the following coverage of the IPOs:

“Pirates are very mobile and very flexible in decision-making,” McAuliffe said. “And have a very democratic system: if the leader is unpopular, he is voted out and goes back to join the rest of the sailors.

“And the whole focus is on profit.”

Benjamin Hornigold is intended to be a “high conviction” investment vehicle, focusing on “five to 10 key trading ideas”, he said, while Henry Morgan is focused on as many as 20-25 key ideas, carrying with it less risk.

You could be forgiven for thinking he is obsessed with pirates – and you’d be wrong.

“My fixation is actually military strategy,” he said, having studied the military campaigns of Julius Caesar, Napoleon and General George Patton, crediting this interest for his approach to investment markets.

Continuing the theme, these companies fitted out a pirate-style office with expensive furniture and a hidden door.

Further reading:

In 2016 I was a freelance contributor to Motley Fool Australia. Just before the HML IPO, my colleagues talked about the fund. I remember someone saying, “shareholders might be walking the plank on that one”. Fast forward a year to early 2017 and Owen Raszkiewicz shot me a message on Skype. “Hey do you remember Henry Morgan?”

“Dunno. Is that the pirate LIC thing?”

“Its’ NTA is up 100%. AFTER paying a 20-cent dividend”

I was curious. +100% years are just not that common, especially not when you’ve paid out 20% of your starting capital. (HML listed with around 97 cents or so in NTA). I started reading the filings.

Reading the 2017 annual report, the first thing I noticed is the majority of assets were classified as Level 3. Here’s the balance sheet from 30 June 2017:

It turns out the managed futures fund had most of its portfolio invested in difficult-to-price unlisted assets. There was a huge performance fee paid, based on the estimated increase in the value of these assets. This market commentary released to the ASX in October 2017 (after the publication of the above balance sheet) has no reference to the performance of the unlisted investments that are a majority of the portfolio.

How I knew:

People always ask me how I “knew” something was up. This was the tell – the precise moment where the lightbulb went on and it clicked for me. This company wasn’t even allowed to invest in unlisted assets – it was specifically prohibited by the prospectus (this was later reversed by shareholder vote).

The valuation of these assets had been marked up based on financial models of their value, resulting in significant performance fees (based on the rise in NTA) payable to the fund manager, John Bridgeman. As a result, much of the easily valued cash flowed out of the vehicles. The NTA was an increasingly larger share of illiquid assets with valuations dependent on assumptions. The mark-ups on the valuations were based at least in part on implied growth so rapid (800% in a year) that probably only one or two companies in the history of the universe have achieved it. More on this later.

The information above is seemingly equivocal. Lots of companies have unlisted investments and some of them go up a lot. But in conjunction with the context around the proposed strategy, i.e. “Fund management vehicle launches a managed futures fund that invests in a prohibited asset class – unlisted equities – where valuations go up a lot in a very short period of time, resulting in the payment of huge fees to the funds management company”, this is where I became highly doubtful and started doing the work.

The rest of the story:

The Level 3 finding kicked off a long process of forensic work – late nights and several thousand hours of research. I couldn’t understand why the assets were valued the way they were. Many of the companies had only been recently incorporated and/or did not appear to have extensive operations (staff on LinkedIn, number of locations, etc).

I owe thanks to a number of people who anonymously contributed to the research.

- One investor sent me the work he and his firm had done to date and offered to lend me an analyst to work on it. He had no position in the stock, just thought it was a market integrity concern, and I’ve never forgotten this.

- A different person arranged for me to receive the entire ASIC documentation of all of the pirate companies.

- #3 helped me test a number of theories around the Brisbane-based businesses and alerted me when my location information was made available through an image that I published.

- A fourth walked me through the “who’s who” of prop trading operations, things to watch for in terms of principal/agent risk (e.g. around segregation of funds) and so on.

The ASIC reports cracked the door wide open as they allowed me to peer into the financials of the unlisted assets. Separately, a Sydney-based adviser, Sulieman Ravell, had been looking into the companies as well. More on Sulieman later.

Why did this take so much time? There was an enormous amount of material to review, including companies with complex (and constantly changing) cross-relationships. Some entities, such as Ashdale, had a history back to the GFC and had previously been the subject of investor lawsuits. I reviewed the content of the lawsuits I could find.

One lawsuit was particularly eye-opening, dealing with unlisted assets in an unrelated case (but with some of the same entities, including Ashdale) going back to 2010. However, as the case was settled, I was not able to investigate further or evaluate the claims made.

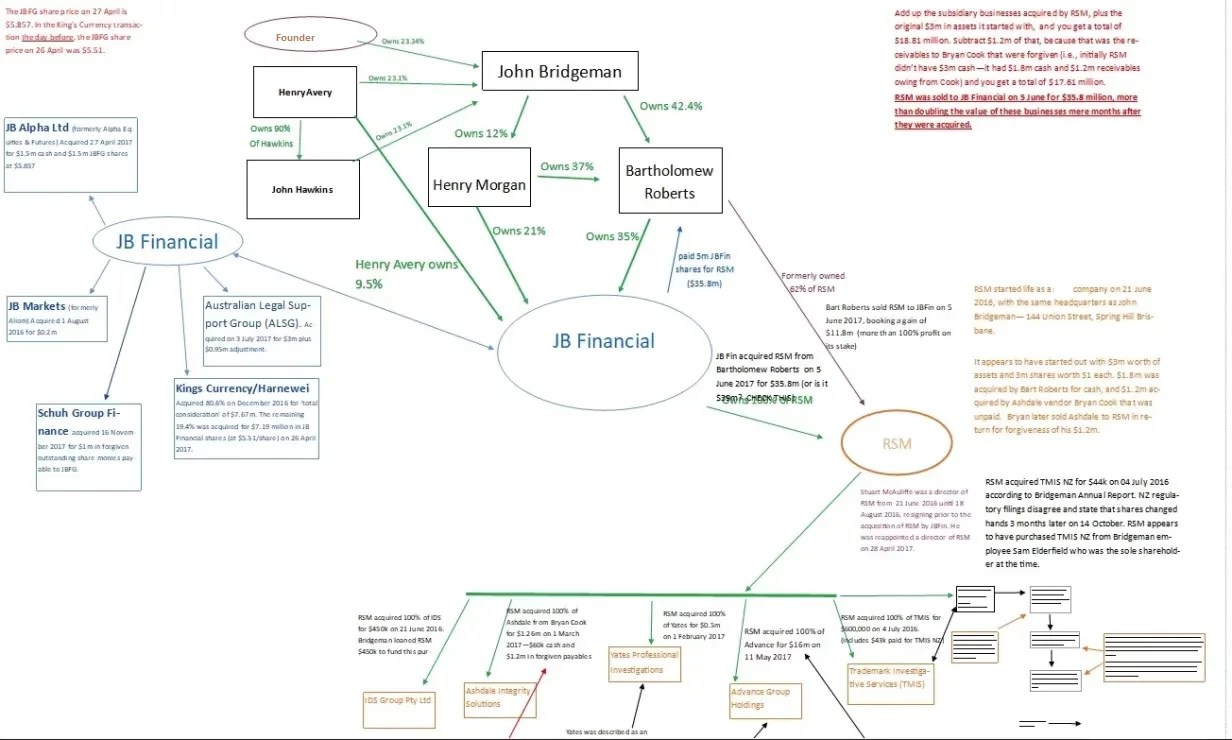

In any event, here is a “simple” version of the unlisted entities:

This is a point-in-time working chart from 2017. It may contain estimates or information that is incorrect.

During the course of the research, I published several reports about the pirate companies and described my concerns.

Fast forward three months to June 2017, and Henry Morgan was suspended by the ASX. Two months later in August, the company released a corrective disclosure that suggested many of my concerns around valuation were accurate. Previously, HML had told the market that its largest unlisted investment had $96m in revenue.

ASIC instructed the company to issue a correction. Annualised revenue at the time was $10m, not $96m, and even this $10m was a proforma figure, based on “entities that the Company controlled or anticipated controlling”. The correction speaks for itself:

Source: Corrective Disclosure to ASX 15 August 2017

The above company was at one point valued on paper at $165 million or more – 25m shares at $6.14 per share. Its primary investments appeared to be prop trading operations and retail forex currency exchanges.

Anyway, after much back and forth between the various exchange operators regarding a number of issues, all three pirate companies were suspended. John Bridgeman and Henry Morgan stayed suspended until they were delisted.

Litigation

Later, in 2018, the pirate companies sued my hosting provider to discover my identity. The AFR covered this here. Looking back, the main thing I would have done differently is to be more discreet. At that time, I still believed the market was well regulated and the regulator would act in a timely way. (Yes, have your little laugh). What’s funny about this story is that, according to the 2022 liquidator’s report, Henry Morgan was likely already insolvent by the time it filed the case against my hosting provider, but I’ll get to that.

Reader, I paid real money for this lesson so that you don’t have to:

*Never* put yourself in a position where you can be sued by a company. The company has more money, more time, and it takes trivial effort to make your life difficult. It is an asymmetric action – for the company it is a job; for you it will consume your entire life.

Trust me.

The Takeovers Panel

In late 2018, one of the other pirate entities made a takeover offer for Benjamin Hornigold. I was ecstatic. I was familiar with the Takeovers Panel from its work on the ADM/Graincorp bid and knew the bidder had made a titanic mistake. I recommended that advisers with clients in BHD apply to the Takeovers Panel to block the proposed bid.

I was unable to assist with the Henry Morgan Application, but later signed a nondisclosure agreement and assisted with the Panel Applications for Benjamin Hornigold.

Again, I won’t go into all of the details as these applications took an enormous amount of work in a very short period of time. The Takeovers Panel declared the circumstances of the bid unacceptable, and some funds were recovered for BHD. Here is a short summary of the decision:

The Panel declared the circumstances unacceptable because (among other things) shareholders had not been given sufficient information to assess the bids, John Bridgeman, Benjamin Hornigold and Henry Morgan failed to adequately advise shareholders in relation to the bids, and certain transactions between John Bridgeman, Benjamin Hornigold and another entity operated as a lock-up device in relation to the bid for Benjamin Hornigold.

The process and decisions can be found here in the “2019” tab: The Takeovers Panel

Credit here goes to the financial advisers who really put in the hard yards, hired (out of their own pocket) the expertise of Corrs Chambers Westgarth, and drove the outcome. I assisted with making the argument/preparing rebuttals and collecting supporting evidence and received a small fee. The Corrs team was outstanding, and their junior lawyers in particular deserve recognition. I vividly remember working 9-5 in my day job, working on my part of the Panel app from 5.30pm until midnight, and then turning it over to the junior lawyers to have a first draft ready for 7am, followed by another round of review ready for submission at 9am.

When people talk about overwork in professional services, these are the scenarios they’re referring to, and the Applications could not have succeeded without these young professionals doing double (triple!) shifts.

The ousting:

After the successful applications, fast-forward again and Sulieman Ravell, Gary Miller, Jon Dixon, and Tony Bennett organised shareholders to vote out existing directors at BHD. After an enormous, concerted effort contacting the shareholder base, Sulieman Ravell, Gary Miller, and Michael Glennon (of Glennon Capital) became new directors of BHD. Then began the difficult work of untangling the mess and figuring out where value could be salvaged. I have no insight into this beyond what is in the public filings, so I would direct readers to the ASX filings for ASX:BHD from 13 June 2019 onwards.

The liquidation:

Following a circuitous series of events that are interesting but would take far too long to cover here, Jon Dixon and others later became plaintiffs in an application to wind up Henry Morgan. The application was approved, but the remarkable part of this process is the judge’s findings. The judge was scathing of Stuart McAuliffe (the investment manager and founder of the pirate companies), finding him an unsatisfactory and evasive witness:

Apologies for the walls of text, but these are worth reading in their entirety:

Unconvincing:

And another:

This is a good one:

Source: MF Lady Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Henry Morgan Limited [2022] FCA 978 (fedcourt.gov.au)

Afterwards, Henry Morgan was liquidated. There has been little to recover so far. The liquidator came to the same view on many of the concerns raised in my original reports in 2017.

Liquidated

There were several highlights from the liquidator’s report, including:

- that HML may have been insolvent from June 2018 if not earlier (~15 months after I published my first report),

- there was a lack of governance and compliance

- the value of investments may have been significantly overstated

- HML deployed the majority of funds for the purpose of investing in & paying fees to companies connected with Stuart McAuliffe

- The final report is confidential (and I have not seen it), but the liquidator appears to be recommending further action to ASIC

I know of at least two people that wrote to ASIC advising them that Henry Morgan was insolvent at the time of the 2018 annual report.

The liquidator’s view of the reasons for failure is also illuminating:

Below are some other interesting highlights from the liquidator’s report.

Difficulties in obtaining books and records:

Unlisted assets increased from $167.02 to $26,667 per share in the space of five months.

When the business became insolvent:

Recommending further action to ASIC:

An inglorious end, to say the least.

In time, I met a decent number of investors in the funds. Their stories ranged from “deeply unfortunate” to “heartbreaking” and aren’t mine to share. I cannot stress this enough: do not invest money you cannot afford to lose, or that you might need in the near term. Equities are a risk asset.

In the end, Stuart McAuliffe and his CFO, Sam Elderfield, were charged with criminal offences by the Department of Public Prosecutions. ASIC release 23-050MR tells the tale. That case is ongoing as at March 2023.

Lessons learned:

I feel like a story like this should end on an uplifting note or with some kind of life lessons delivered. Alas, there is no uplifting note, and the lessons are the same as they ever were.

- Always ask why the opportunity exists

- And why is it coming to you, random person on the internet, in the world’s most competitive marketplace?

- Governance is really important

- A company can spend shareholder money as it pleases if oversight is ineffective

- As an investor, it’s very difficult to stop a company from doing what it wants, or what it is incentivised to do

- Good journalists are a national treasure

- The Takeovers Panel is Australia’s finest institution

- Don’t let greed drive your emotions

- Don’t invest money you can’t afford to lose

- Always ask whether it is too good to be true

- If it sounds too good to be true, maybe it is?

Lastly, and this is a really important suggestion I find myself giving more and more in recent years:

Consider whether you are competent to own shares, except the level of competence is what you would require if “own shares” was replaced with “perform heart surgery”.

Which is a really complicated way of saying that 97% of people should just buy an index fund, and no, you are not the 3%. Investing is hard, the marketplace is competitive, there are few free lunches, and your default assumption should be that you don’t have an edge.

Final note:

And that’s all she wrote folks. Nearly six years later, the flaming wreck of one of the most disappointing sagas I’ve seen in my fifteen years investing. The one plus; I got pretty good at looking at risky companies like Trimantium Growthops, Updater, and Halo Technologies.

Stay safe out there.

Further Reading:

- Directors Intentions following Board change – ASX 13 June 2019

- The pyrrhic victory of the pirate mutineers – AFR, Jun 2020

- ASIC’s gripes with skyrocketing pirate fund unearthed – AFR, July 2020

- ‘Shadow director’ probe in pirate fund business – AFR, Dec 2020

- Henry Morgan – Pirate investor Stuart McAuliffe faces mutiny – AFR, Dec 2018

I have no, and have never had any, financial position in any company mentioned. I have no ongoing financial relationship with any company or individual mentioned. This is a disclosure and not a recommendation.

No Comments